Robert Graham Rolo Calf Hair & Leather Slip-on Sneakers Reviews

| Robert I | |

|---|---|

| |

| Duke of Normandy | |

| Reign | 1027–1035 |

| Predecessor | Richard Three |

| Successor | William I |

| Born | 22 June 1000 (1000-06-22) Normandy, French republic |

| Died | 3 July 1035 (1035-07-04) (aged 35) Nicaea |

| Effect |

|

| Business firm | Normandy |

| Father | Richard II, Knuckles of Normandy |

| Mother | Judith of Brittany |

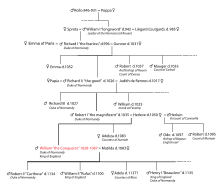

Robert the Magnificent (French: le Magnifique;[a] 22 June 1000 – one–3 July 1035) was the duke of Normandy from 1027 until his death in 1035.

Attributable to uncertainty over the numbering of the dukes of Normandy he is ordinarily called Robert I, but sometimes Robert 2 with his antecedent Rollo as Robert I. He was the son of Richard II and brother of Richard III, who preceded him as the duke. Less than a twelvemonth after his father's expiry, Robert revolted confronting his brother's rule, simply failed. He would afterwards inherit Normandy after his brother's death. He was succeeded by his illegitimate son, William the Conquistador, who became the starting time Norman male monarch of England in 1066, following the Norman conquest of England.

Biography [edit]

Robert was the son of Richard 2 of Normandy and Judith, daughter of Conan I, Duke of Brittany. He was too grandson of Richard I of Normandy, bang-up-grandson of William I of Normandy and great-smashing grandson of Rollo, the Viking who founded Normandy. Before he died, Richard II had decided his elder son Richard III would succeed him while his 2d son Robert would become Count of Hiémois.[1] In August 1026 their father Richard 2 died and Richard III became knuckles, merely shortly later Robert rebelled against him, and was afterwards defeated and forced to swear fealty to Richard.[two]

Early reign [edit]

When Richard III died a year later on, in that location were suspicions that Robert had something to exercise with his death. Although nothing could exist proven, Robert had the well-nigh to proceeds.[3] The civil war Robert I had brought confronting his brother Richard Iii was notwithstanding causing instability in the duchy.[3] Private wars raged between neighbouring barons, which resulted in a new aristocracy arising in Normandy during Robert's reign.[iii] It was likewise during this time that many of the lesser dignity left Normandy to seek their fortunes in southern Italy and elsewhere.[3] Shortly later assuming the duchy, possibly in revenge for supporting his brother against him, Robert I assembled an army against his uncle, Robert, Archbishop of Rouen and Count of Évreux. A temporary truce allowed his uncle to leave Normandy in exile simply this resulted in an edict excommunicating all of Normandy, which was only lifted when Archbishop Robert was allowed to return and his countship was restored.[4] Robert besides attacked another powerful churchman, his cousin Hugo III d'Ivry, Bishop of Bayeux, banishing him from Normandy for an extended period of time.[5] Robert also seized a number of church backdrop belonging to the Abbey of Fecamp.[half dozen]

Outside of Normandy [edit]

Despite his domestic troubles, Robert decided to arbitrate in the civil state of war in Flanders between Baldwin Five, Count of Flanders and his father Baldwin IV, whom the younger Baldwin had driven out of Flanders.[7] Baldwin V, supported by king Robert II of French republic, his begetter-in-law, was persuaded to brand peace with his father in 1030 when Duke Robert promised the elder Baldwin his considerable war machine support.[7] Robert gave shelter to Henry I of France against his mother, Queen Constance, who favoured her younger son Robert to succeed to the French throne later his begetter Robert II.[8] For his assistance Henry I rewarded Robert with the French Vexin.[8]

In the early 1030s Alan Three, Duke of Brittany began expanding his influence from the area of Rennes and appeared to have designs on the area surrounding Mont Saint-Michel.[nine] After sacking Dol and repelling Alan'south attempts to raid Avranches, Robert mounted a major entrada against his cousin Alan Iii.[9] However, Alan appealed to their uncle, Archbishop Robert of Rouen, who then brokered a peace betwixt Duke Robert and his vassal Alan Iii.[9] His cousins, the Athelings Edward and Alfred, sons of his aunt Emma of Normandy and Athelred, Male monarch of England, had been living at the Norman Court and at one point Robert, on their behalf, attempted to mount an invasion of England but was prevented in doing then, it was said, by unfavourable winds,[10] that scattered and sank much of the fleet. Robert made a rubber landing in Guernsey. Gesta Normannorum Ducum stated that King Cnut sent envoys to Duke Robert offer to settle half the Kingdom of England on Edward and Alfred. Subsequently postponing the naval invasion, he chose to also postpone the conclusion until later he returned from Jerusalem.[eleven]

Church and pilgrimage [edit]

Robert's attitude towards the Church had inverse noticeably certainly since reinstating his uncle'south position equally Archbishop of Rouen.[12] In his attempt to reconcile his differences with the Church, he restored belongings that he or his vassals had confiscated, and by 1034 had returned all the backdrop he had earlier taken from the abbey of Fecamp.[13]

Afterward making his illegitimate son William his heir, he set out on pilgrimage to Jerusalem.[14] Co-ordinate to the Gesta Normannorum Ducum he travelled by mode of Constantinople, reached Jerusalem, fell seriously ill and died[b] on the render journey at Nicaea on two July 1035.[xiv] His son William, aged about eight, succeeded him.[15]

According to the historian William of Malmesbury, decades subsequently his son William sent a mission to Constantinople and Nicaea, charging it with bringing his begetter'southward body dorsum to Normandy for burial.[16] Permission was granted merely, having travelled as far as Apulia (Italia) on the render journeying, the envoys learned that William himself had meanwhile died.[16] They then decided to re-inter Robert'south body in Italy.[16]

Concubines and children [edit]

By his mistress or concubine, Herleva of Falaise,[17] [18] he was father of:

- William the Conqueror (c. 1028–1087).[xix]

By Herleva or possibly another concubine,[c] [xx] he was the father of:

- Adelaide of Normandy, who married firstly, Enguerrand II, Count of Ponthieu.[21] She married secondly, Lambert Ii, Count of Lens, and thirdly, Odo Ii of Champagne.[22]

Notes [edit]

- ^ He was as well, although erroneously, said to have been chosen 'Robert the Devil' (French: le Diable). Robert I was never known by the nickname 'the devil' in his lifetime. 'Robert the Devil' was a fictional character who was confused with Robert I, Knuckles of Normandy erstwhile most the end of the Centre Ages. Come across: François Neveux, A Brief History of the Normans, trans. Howard Curtis (Constable & Robinson, Ltd. London, 2008), p. 97 & n. 5.

- ^ It was reported by William of Malmesbury (Gesta regum Anglorum, Vol. i, pp. 211–12) and Wace (pt. iii, II, 3212–14) that Robert died of poisoning. William of Malmsebury pointed to a Ralph Mowin as the instigator. See: The Gesta Normannorum Ducum of William of Jumièges, Orderic Vitalis, and Robert of Torigni, Ed. & Trans. Elizabeth M.C. Van Houts, Vol. I (Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1992), pp. 84–5, due north. ii. However, it was common in Normandy during the eleventh century to aspect any sudden and unexplained death to poisoning. See: David C. Douglas, William the Conqueror (University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1964), p. 411

- ^ The question of who her mother was seems to remain unsettled. Elisabeth Van Houts ['Les femmes dans fifty'histoire du duché de Normandie', Tabularia « Études », n° 2, 2002, (10 July 2002), p. 23, n. 22] makes the argument that Robert of Torigny in the GND II, p. 272 (one of iii mentions in this volume of her being William'due south sis) calls her in this case William's 'uterine' sister' (soror uterina) and is of the opinion this is a mistake like to 1 he made regarding Richard II, Duke of Normandy and his paternal one-half-brother William, Count of European union (calling them 'uterine' brothers). Based on this she concludes Adelaide was a daughter of Knuckles Robert by a different concubine. Kathleen Thompson ["Being the Ducal Sis: The Role of Adelaide of Aumale", Normandy and Its Neighbors, Brepols, (2011) p. 63] cites the aforementioned passage in GND equally did Elisabeth Van Houts, specifically GND II, 270–ii, just gives a unlike stance. She noted that Robert de Torigni stated hither she was the uterine sister of Duke William "so we might perchance conclude that she shared both mother and father with the Conquistador." Merely as Torigni wrote a century after Adelaide's birth and in that same sentence in the GND made a genealogical fault, she concludes that the identity of Adelaide'southward mother remains an open question.

References [edit]

- ^ The Gesta Normannorum Ducum of William of Jumieges, Orderic Vitalis, and Robert of Torigni, Vol. Ii, Books V-VIII, ed. Elisabeth Chiliad.C. Van Houts (Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1995), pp. 40–1

- ^ David Hunker, The Normans, The History of a Dynasty (Hambledon Continuum, London, New York, 2002), p. 46

- ^ a b c d David C. Douglas, William the Conqueror (University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1964), p. 32

- ^ David Crouch, The Normans, The History of a Dynasty (Hambledon Continuum, London, New York, 2002), p. 48

- ^ François Neveux. A Brief History of The Normans (Constable & Robbinson, Ltd, London, 2008), p. 100

- ^ David Crouch, The Normans, The History of a Dynasty (Hambledon Continuum, London, New York, 2002), p. 49

- ^ a b David Crouch, The Normans, The History of a Dynasty (Hambledon Continuum, London, New York, 2002), pp. 49–50

- ^ a b Elisabeth Grand C Van Houts, The Normans in Europe (Manchester Academy Printing, Manchester and New York, 2000), p. 185

- ^ a b c David Crouch, The Normans, The History of a Dynasty (Hambledon Continuum, London, New York, 2002), p. 50

- ^ Christopher Harper-Bill; Elisabeth Van Houts, A Companion to the Anglo-Norman World (Boydell Printing, Woodbridge, UK, 2003), p. 31

- ^ The Gesta Normannorum Ducum of William of Jumièges, Orderic Vitalis, and Robert of Torigni, Ed. & Trans. Elizabeth G.C. Van Houts, Vol. I (Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1992), pp. 78–80

- ^ François Neveux. A Cursory History of The Normans (Constable & Robbinson, Ltd, London, 2008), p. 102

- ^ François Neveux. A Brief History of The Normans (Constable & Robbinson, Ltd, London, 2008), p. 103

- ^ a b The Gesta Normannorum Ducum of William of Jumièges, Orderic Vitalis, and Robert of Torigni, Ed. & Trans. Elizabeth M.C. Van Houts, Vol. I (Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1992), pp. eighty–5

- ^ François Neveux, A Brief History of the Normans, trans. Howard Curtis (Constable & Robinson, Ltd. London, 2008), p. 110

- ^ a b c William M. Aird, Robert Curthose, Knuckles of Normandy: C. 1050–1134 (Boydell Press, Woodbridge, United kingdom, 2008), p. 159 due north. 38

- ^ The Gesta Normannorum Ducum of William of Jumièges, Orderic Vitalis, and Robert of Torigni, Ed. & Trans. Elizabeth M.C. Van Houts, Vol. I (Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1992), p. lxxv

- ^ "William I | Biography, Reign, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica . Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- ^ David C. Douglas, William the Conqueror (University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1964), p. 15, passim

- ^ David C. Douglas, William the Conquistador (Academy of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1964), pp. 380–1 noting she may or may not be Herleva's girl but probably is

- ^ George Edward Cokayne, The Consummate Peerage of England Scotland Republic of ireland Great Great britain and the United Kingdom, Extant Extinct or Dormant, Vol. I, ed. Vicary Gibbs (The St. Catherine Press, Ltd., London, 1910), p. 351

- ^ David C. Douglas, William the Conqueror (University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1964), p. 380

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_I,_Duke_of_Normandy

0 Response to "Robert Graham Rolo Calf Hair & Leather Slip-on Sneakers Reviews"

Post a Comment